Tags

Bad Boys, bamboccianti, Baroque, Bernini, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Italy, Rome, Travel

Caravaggio, with his dark masterpieces and epic, troubled life, is the quintessential bad boy of the Baroque. But as I had a chance to learn recently, he wasn’t alone. He may have paved the way but there were a whole passel of tricksters, flirts and provocateurs who followed in his trouble-making footsteps.

At the Villa Medici in Rome, until January 18, 2015, you can see an exhibit titled I Bassifondi del Barocco: La Roma del Vizio e della Miseria (Slums of the Baroque: The Rome of Vice and Poverty). The exhibit costs 12€ without a student discount but it’s worth the price.

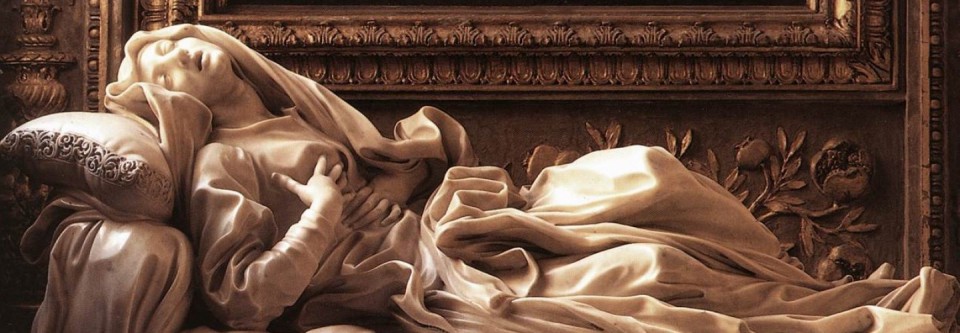

The show highlights a group of painters I wasn’t familiar with (I’m not an art historian) but since I’m always Searching for Bernini, learning about these bad boys made me giddy, especially since my 400-year-old boyfriend was hardly a bad boy. He had his moments — like that time he hired someone to slash his cheating mistress’ face. But as far as the establishment and his patrons were concerned, he kept them happy with his gorgeously idealistic sculptures, paintings and grandiose architecture — all for the glory of the Mother Church.

But these guys, mostly Flemish and Dutch painters and engravers who’d flocked to Rome in the early 17th century, weren’t interested in toeing the party line. They were known as the Bentvueghels (“birds of a feather” in Dutch — see, they really did “flock” to Rome).

This society of artists had a tradition, much like a modern fraternity, to take a nickname (or “bent” name) when they joined, after much hazing and drinking — bacchanals that could last 24 hours.

Their erstwhile leader was Pieter van Laer, known as “Il Bamboccio,” or “ugly puppet,” since apparently he was no prize to look at. He initiated a style of painting — and earned followers of his style — that became known in Rome as I Bamboccianti.

The painters, who included Jan Both, Karel Dujardin, Jan Miel, Johannes Lingelbach, Michelangelo Cerquozzi and Bartolomeo Manfredi, among others, revelled in painting scenes of daily life, often capturing the disintegration of ancient Roman ruins, while normal life went on around it, paying the old world no mind.

And, just as Caravaggio had done a few years before, they painted and revered the figure of Bacchus, the god of wine.

But they didn’t worship Bacchus only because they were party animals who liked to drink. As the exhibit explains, drunkenness could be seen as a source of creative frenzy and secret knowledge (in vino veritas), and these men wanted to capture that in their art — and they did through a prolific outpouring of work.

Part of what they wanted to show was not just the declining, disintegrating beauty of their adopted home, but the Truth of life in the Eternal City. So they focused on commoners, prostitutes and violence, which was a side of Rome that hadn’t been previously captured on canvas so boldly.

A favorite setting was the local tavern, a place these painters knew well from personal experience. Excessive drinking, gambling and eroticism were the name of the game in these tavern. They even went so far as to put explicitly insulting gestures in their paintings (think of the modern “flipping the bird,” only more sexual!).As the exhibit points out, their paintings evoke in the viewer a feeling of both horror and fascination: Essentially these bad boys liked to paint train wrecks to draw in the rubberneckers. But they didn’t just do it for fun — they had a higher purpose. They wanted to show within the safe confines of “fiction” all the thrills and dangers of a dissolute life, to give the viewer a safe window with which to experience some of what they themselves had experienced.

When not painting the wild life inside taverns, they ventured onto the streets and into the slums to capture the underworld of Rome: Gypsies, pickpockets and courtesans plying their trade. In the two paintings below, Manfredi’s, and Caravaggio’s earlier rendition, a gypsy seems to read the palm of an aristocrat…but what may really be happening is the gypsy is stealing a ring off her victim’s finger.

Or they put these characters within a bucolic rural scene. In this way, they also helped promote the idea of the dignity of poverty. They turned the spotlight on the little person.

In this way, the Bamboccianti subverted the traditional codes of art admired in Rome at the time, as well as the accepted standards of beauty, and instead showed life as it truly was: filled with slums, nightlife, danger… and a terrible beauty all its own.

Fascinating piece. Well written and fun to read. People don’t realize the soft underbelly of Italian culture. It’s never always been Mediterranean pine trees and mozzarella. Serious poverty and debauchery has existed on this peninsula for centuries but I didn’t know there were so many artists to capture it.

LikeLike

Pingback: Caravaggio’s Whores: The Courtesans of Rome Part II | Searching For Bernini