Tags

architecture, Federico Zuccari, Gianlorenzo Bernini, Italy, Piazza di Spagna, Roman, Rome, secrets of rome, Spanish Steps, Travel, Trinità dei Monti, Vatican City

Statues talk, humans are available to rent,

and sometimes doorways scream…

There’s so much to learn in Rome that it can be intimidating when I think about all I don’t know. But as the Italians tell me so often, especially when I stress out about not being able to speak, “Piano, piano!” Slowly, slowly….

So, every chance I get to absorb some new info about the city and its history I’m grateful, and concentrate fiercely on trying to remember it all.

After Italiano class one day this week, my school, Italia Idea, offered a two-hour walking tour around the neighborhood where it’s located, near the famous Piazza di Spagna. Our guide, Paolo, is one of the teachers and an official tour guide (in Italy, becoming a registered tour leader isn’t easy; it requires taking difficult oral and written exams).

It turns out Paolo has studied the works of my 400-year-old boyfriend, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and seems as fascinated with his art and flamboyant personality as I am. So, here are some of the secrets of Rome I learned from Paolo on our tour, conducted in Italiano. On a warm spring day, we started off east of the Steps and wound up a cobblestone street, Via Gregoriana, to a look-off point on a hill above where an interesting palazzo sits…

1. The walls have ears, and here the doorways scream. The Palazzo Zuccari is an odd building designed at the turn of the 16th century by Federico Zuccari, an artist from Urbino (his frescos can be found in the Santa Maria del Fiore church). He built the palazzo to celebrate artists. Looking at the building from the front it seems a nice, old palace. It changed hands several times and during the mid-1600-1800s—the period when upper class Europeans took a Grand Tour—it became an inn that hosted artists like Joshua Reynolds and Jacques-Louis David.

Paolo informed us that the palazzo originally had an amazing view across what were rolling hills and gardens that descended down to what is now the Piazza di Spagna. Where this palazzo gets a little odd, however, is when you walk around and look at the side of the building, where an entrance and a couple of windows are framed by screaming, open mouths.

Apparently these were meant to intimidate visitors so they knew that entering the palazzo was an important act, and not to be taken lightly. Zuccari had used a similar depiction years before to evoke Dante’s doors to Hell. Welcome! Come on in! (Or, actually, don’t, unless you’re a top-level German scholar specializing in Italian and Roman art of the Renaissance and Baroque periods who’s won an exclusive fellowship to study at the Hertzian Library, which is now housed there.)

2. The Spanish Steps are both “modern” and “natural.” At least that’s how Paolo describes them—and when a country’s history extends back more than 2000 years, steps built in the 1700s seem new. From the Palazzo, we walked by the Trinità dei Monti church and started down the Spanish Steps.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the area around what is now Piazza di Spagna was considered the center of Rome. There were a few bustling streets where commerce happened, and the area was home to several grand palazzos, surrounded by countryside or gardens. What we know as the Spanish Steps didn’t exist until the 1720s, when they were built to follow the natural flow of the land and hills around the piazza. They were meant to be organic and naturalistic, a favorite theme of the Baroque. So if you really look at the steps, all 138 of them, you can see how the architect, Francesco de Sanctis, designed them to flow down the hill from Trinità dei Monti, following the shape of the land. At different points of the year, the steps are covered in flowers—today the Bougainvillea is bountiful.

3. Rome is a dual capital. More Italian politics: Rome is not only the capital of Italy, it is also the capital of Vatican City. The church is its own city-state. In fact, it’s the smallest internationally recognized independent state in the world. And as Paolo informed us, all countries with representatives in Rome actually have two embassies, one for Italy and one for the Vatican. One of the palazzos in the square is the Spanish Embassy to the Holy See, and it’s from the embassy that the piazza takes its name. In the 17th century, the area around the embassy was considered Spanish territory.

4. That boat fountain tells a true story. Bernini first learned to sculpt at the feet of his father, Pietro Bernini. Pietro earned a commission from Pope Urban VIII to create the Fontana delle Barcaccia in the middle of the Piazza. Bernini the Elder reportedly took his inspiration from the flooding of the Tiber in 1598 (incidentally, the year my Bernini was born), when a small boat actually did get stranded in the area.

5. Human models were available for rent. Models here! Get your models here! The area around Piazza di Spagna was a kind of Soho of its time: Artists of all types lived and worked here at different times—John Keats died in the building to the right of the Steps in 1821, and it’s now a museum dedicated to him and Percy Bysshe Shelley. In the 16th and 17th centuries, young Romans would stand in the piazza hoping to be hired by artists who needed people to pose for them. I love the idea of gorgeous, young Italians sucking in their cheeks and flaunting their beauty just waiting to be immortalized by Caravaggio or even Bernini (although I think he was his own favorite model). In fact, the reason many of the faces look alike in different Renaissance artists’ paintings is probably because the artists hired the same models. Oops! I wonder if they got into fights: “Hey, you stole my Virgin Mary!”

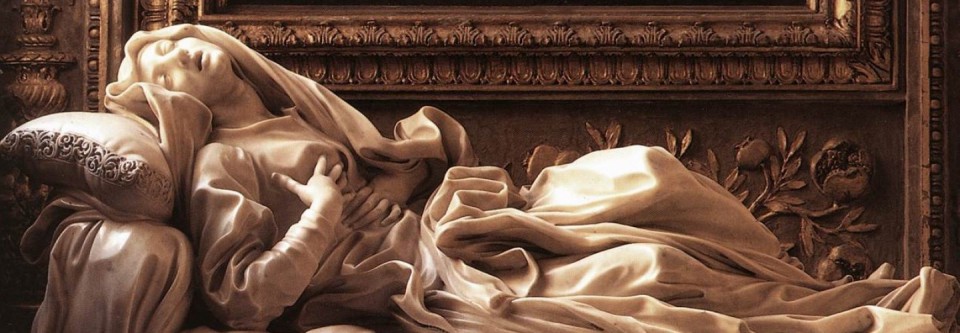

6. Talking statues. No, not the models I mentioned above. Throughout Rome, and on our walk we passed by the Café Canova Tadolini at 150 Via Babuino. (I’ll check out the restaurant in future—you eat among the statues.) Outside, sits a statue that perhaps gave the street (Babuino means baboon) its name, because the reclining figure ain’t so pretty.

The statue is one of several around Rome where citizens would come to leave notes complaining about things they would never be able to out loud: “My taxes are too high!” “The Pope doesn’t give us enough bread!” Back in Bernini’s time (and before…and after), Romans had to guard their tongues (see my earlier post on “dissimulation”). If they spoke against the Church openly, the punishments were harsh and sometimes deadly. But these statues provided one outlet for the frustrated to voice complaints—and so they were called talking statues.

Stay tuned for Part II of the walk around the Piazza di Spagna….

Spectacular, Lisa!!! I love this. What do you plan to do with your completed project (if, that is, it can ever be completed!)? Great work…love the photos.

Small point: does not “capitol” mean a building, while “capital” means a town? I’m not sure of this and haven’t looked it up (something stuck in my head from high school, probably).

LikeLike

D’oh I actually looked up Capitol and still couldn’t really tell! You’re probably right tho… Thanks!

LikeLike

What does “moderation” mean?

LikeLike

It means I have to approve comments before they’re posted. 🙂

LikeLike

Lisa, Great job, as always. Oh, I hadn’t seen the screaming doorway before…love it! Will check it out next week. See you soon. t

LikeLike

Grazie Toni! Let me know if/when you’re in Roma.

LikeLike

arent they azalea plants on the Spanish Steps, not bougainville ?

LikeLike